Many teams have at least a moderate ability to plan and control their time. They’re able to say, “We will work on these things over the coming sprint,” and have a somewhat reasonable expectation of that being the case.

And that’s the type of team we encounter in much of the Scrum literature–the literature that says to plan a sprint and keep change out.

But what should teams do when change cannot be kept out of a sprint?

In this post, I want to address this topic for two different types of teams:

- A team that has occasional, but not excessive, interruptions

- A team that is highly interrupt-driven

Planning with a Moderate Margin of Safety

Many teams will benefit from including a moderate amount of safety into each sprint. Basically, these teams should not assume they can keep all changes out of the sprint. For example, a team might want to leave room when planning a sprint for things like:

- Fixing critical operational issues, such as a server going down

- Fixing high-severity bugs

- Doing first- or second-level tech support

There could be many other similar examples. Consider your own environment. You want to try to set a high threshold for what constitutes a worthy interruption to a sprint. Teams really do best when they have large blocks of dedicated time that will not be interrupted.

To accommodate work like this, all a team needs to do is leave a bit of buffer when planning the sprint. Let’s see how that works.

The Three Things That Must Go into Each Sprint

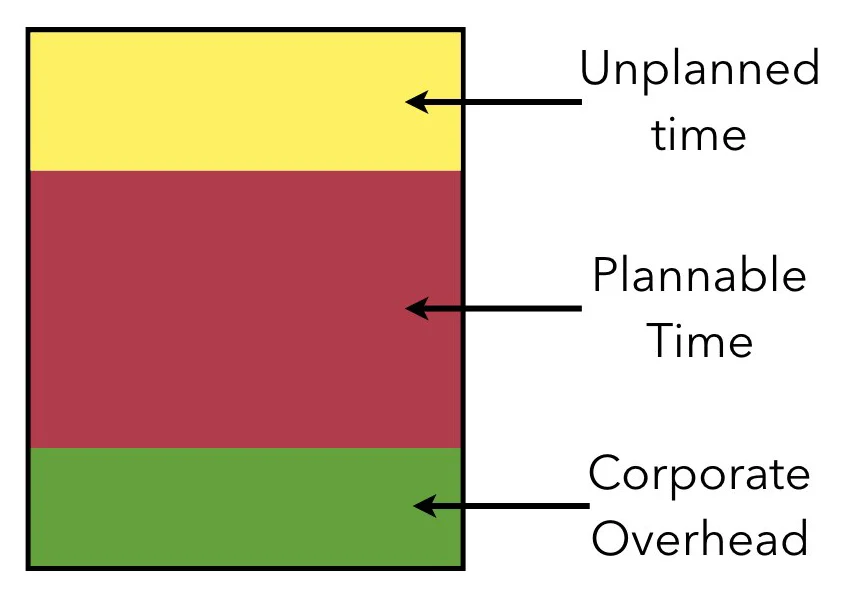

I think of a sprint as containing three things: corporate overhead, and plannable and unplanned time. I think of this graphically as shown in Figure 1.

Corporate overhead is that time that goes towards things like all-company meetings, answering emails from your past project, attending the HR sensitivity training and so on. Some of these activities may be necessary, but in many organizations, they consume a lot of time.

I put Scrum meetings (planning, daily scrum, etc.) in the corporate overhead category as well.

Plannable time is the second thing that goes into a sprint. This is the time that belongs collectively to the team.

But the team does not want to fill the entire remainder of the sprint with plannable time. The team needs to acknowledge the need to leave room for some amount of unplanned time.

Unplanned time goes towards three things:

- Emergencies

- Tasks that will get bigger than the team thinks

- Tasks that no one thinks of during the sprint planning meeting

The Appropriate Percentages

After each sprint, consider how well the unplanned time the team allocated matched the unplanned time the team needed for the sprint. And then adjust up or down a bit for the next sprint. This is not something a team can ever get perfect.

Instead, it’s a game of averages. The team needs to save the right amount of time for unplanned tasks on average. Then some sprints will have more unplanned tasks occur and some sprints will have fewer.

When fewer occur, the team should get ahead on their work. so they’re prepared for when more unplanned tasks occur.

Team With Highly Interrupt-Driven

The preceding advice works well for the majority of agile teams–those that are only interrupted a moderate amount. Some teams, however, are highly interrupt-driven.

Again, I want to resist putting actual percentages on the regions in Figure 1, but I’m describing a situation in which the area of “unplanned time” becomes much larger than shown.

I actually want to talk about the cases in which unplanned time becomes the dominant of the three areas. Such teams are highly interrupt-driven.

These teams still want to include space in their sprints for unplanned time. But there are usually a few other things you may want to consider if you are on a highly interrupt-driven team.

First, you may want to adjust your sprint length. One option is to go with a long sprint length. Increasing sprint length has the benefit of making the rate of interruption more predictable because the variance will not be so great from sprint to sprint.

To see how that works, imagine you chose a one-year sprint. (Don’t do that!) It’s easy to imagine with such long sprints, the fluctuations a team faces with short sprints will wash out. Sure, this year (this sprint) might have more interruptions than last year (last sprint), but it’s such a long period that the team has time to recover from any excessive fluctuations.

The other option is to go with short, one-week sprints and just live with the unpredictability. The team will be less able to assure bosses “we will be done with this” by a given period, but I find that to be a worthwhile tradeoff.

Second, a highly interrupt-driven team should make sprint planning a very lightweight activity.

Sprint planning should be a quick effort to grab a few things the team thinks it can do in the coming week, and that’s that. It should be a very minimal effort–15 or 30 minutes for many teams.

To illustrate this, think about planning a party, and imagine a spectrum with planning a wedding reception on one end. That’s some serious party planning. At the other end of the spectrum is inviting some friends over tonight to watch the big game on TV. To plan that, I’m going to check the fridge for beer and order a pizza. That’s a different level of party planning.

Sprint planning for a highly interrupt-driven team should be much more like the latter–quick, easy and just enough to be successful.